It was 160 years ago this month that John and Elizabeth Heckart and their family came to Algona. They had come to join the community founded by their daughter, Sarah Heckart Call, and her husband, Asa. Another daughter, Emma, arrived with them.

First published in the Upper Des Moines Republican on December 13, 1911, the intriguing story below was handwritten by Emma Heckart at the request of Benjamin Reed, then serving as president of the Kossuth County Historical Society. Portions of the story were used by Mr. Reed in his History of Kossuth County published in 1913, but her memories are worth reading in their entirety.

First published in the Upper Des Moines Republican on December 13, 1911, the intriguing story below was handwritten by Emma Heckart at the request of Benjamin Reed, then serving as president of the Kossuth County Historical Society. Portions of the story were used by Mr. Reed in his History of Kossuth County published in 1913, but her memories are worth reading in their entirety.

REMEMBRANCE OF

EARLY ALGONA

By: Miss Emma Heckart

In my far away

home in Florida comes a request from the president of the Kossuth County

Historical Society for a paper on the early history of Algona. The story has often been told by abler pens

than mine, but as it is ever a pleasure to recall those days, I will, at the

risk of being tiresome, tell again the little that I know.

ARRIVAL

It was on the

10th of May, 1856, that we pulled into Algona. We had made a five hundred mile trip from

Elkhart, Indiana, with a four-ox team, in just seven weeks’ time. I was but a child then, eleven years old, and

can with certainty recall but little of the order in which the settlers moved

in and built their houses, but the first glimpse I had of the place is firmly

fixed in my memory.

The log house

on our left, which could be plainly seen with the naked eye, was known as the

“Joe Moore cabin” and a right hospitable place it must have been, for inside

could be seen Jerome Stacy, W. H. Ingham, L. H. Smith, Abe Hill, Jake Cummins,

Father Taylor, the Joe Thompson family, and I don’t know how many more.

There were

eight of us—my father and mother, Michael Fisher, my mother’s brother, who died

the following winter and was the first settler buried in Riverview Cemetery, a

teamster, who had come with us from Indiana, a sister, two brothers and myself,

and I have no doubt but that we too could have found shelter under the same

roof if we had applied for admission, but we were aiming for another

point. Straight to the northwest we

steered our craft, over cementless walks and houseless lots and soon came in

sight of another cabin—the home of my sister, Mrs. Call, who had preceded us by

nearly two years, and whom we were all anxious to see. Love is stronger than gold or lands and it

was more through her letters of entreaty that “we come to Algona and live near

her” than the lure of Uncle Sam’s broad prairies that had urged us on through

spring rains, mud and slush and treacherous sloughs and was even now bringing

us to her cabin door.

The oxen were

too slow for me and jumping out while the wagon was visibly moving, I rushed

for the cabin door into the middle of the room, but no Sarah could be

seen. Standing there and wondering where

she could be I heard a suspicious little sniffle behind the door. Looking back I found my sister, overcome with

joy at meeting all again, she had hidden herself and was crying and laughing

simultaneously.

Many and long

have the years been, dear sister since we mingled our tears behind your cabin

door, but they will be fewer and shorter till we meet again at heaven’s open

portal.

I had two other

sisters then but neither one quite so dear as Sarah. She had nursed me in my infancy, played with

me in childhood, and taught me to read, knit and sew. She was at once mother, sister, playmate and

friend. Sacred to me is her memory.

A few rods east

of the Call cabin, showing through the trees and hazel thicket, stood the four

walls of our own. Kind neighbors had,

before we arrived, raised the building and cut openings for one door and half a

window. We stayed with the Calls one

week till our cabin was finished and then took possession. We had a fine garden that year—everything

seemed to thrive on the rich Iowa soil and father and mother and brother Cal

raised an abundance of seed-corn, potatoes and watermelons.

INDIAN SCARES

One day after we had been living in our new home for about a week, a tent was pitched a few rods east of our cabin. Like a big mushroom it had sprung up in a few hours. Men and boys, women and girls, dogs and horses were moving in lively commotion. Hezekiah Henderson had come to town, and judging by the goods he had brought with him, had come to stay. I don’t remember the length of time they lived in this tent, but “Ki” was an energetic man and before the terrible winter of “56-7 had set in he had built a commodious hewn log cabin near the present site of the Thorington Hotel and had his numerous family warmly housed. It was the largest cabin in town and was a much needed place, for here the homeless young men who were seeking their fortunes in primitive Algona, found a good boarding place and travelers were hospitably entertained, and here one winter night the whole town rendezvoused for safety. It was in the winter of ’57, shortly after the massacre at Spirit Lake, we were aroused from our slumbers by a rap at the door, and someone in a fearfully low and blood-curdling voice told us to “get up quick, the Indians were just on the other side of the river, that they could see their camp fire with figures moving in front of it, that we must all go to Ki Hendersons.” It is needless to say we hurried. Excitement and fear prevented us making very great headway, but as fast as we were able sought refuge in the new cabin. The women and children were hustled off upstairs. Men with guns filled the room below, and others stood guard outside, with the understanding that if anyone fired off a gun without orders, he would be shot.

Fearfully we

waited, expecting any moment to hear the firing of guns and the whoop of

Indians, but not a sound was heard, nor a funeral note. We upstairs people grew tired listening and

waiting and one by one lopped over on to beds, chairs or floor and went to

sleep. When morning dawned we woke and

quietly went to our homes, thankful and surprised that we were still living.

That camp fire

with the figures moving in front of it was a singular vision. Captain Ingham and a few others with him

crossed the river that night to the north of the place where the light seemed

to be, but found no fire or Indians. And

I afterwards learned that people living on the West Branch of the Des Moines

river, twenty miles away, on the same night, saw the same light still west of

them as far as eye could see.

Another

comfortable and well built cabin was built in the summer of ’56 by Father

Taylor. Here he lived, and from here,

like the Master, who it was his delight to serve, went about doing good. He gave time, money and comfort for the

people among whom he had cast his lot.

Thus the log

cabin era of Algona was ended. It was

overlapped and in some instances reached far into the frame house period, but

these five cabins were all, I think, that was ever built on the town site. J. Ellison Blackford had built on the west

border of town in the summer of ’55, but it was over the line. Several young men and few newcomers had put

up log residences on their claims, but a steam saw mill, the boiler of which we

had passed fast stuck in a slough on our way here from near Independence, soon

supplied the people with a more easily manipulated building material, and time

has effectually covered the last traces of these early Algona homes.

The summer of

’56 was particularly prosperous and hopeful.

The crops were fine; the seed corn and potatoes yielded abundantly and

our garden was a surprise—a source of pleasure and profit.

Everything

seemed to thrive and everybody seemed pleased that they had come to

Algona. But if fortune’s pendulum swung

high it fell accordingly low during the winter that followed. Never since have we seen the snow so deep nor

the cold so intense. Thermometers often

registered 40 degrees below zero and snow as four feet deep on the level with

drifts twenty feet high. To keep warm

and get enough to eat were the mighty problems that faced us. Like the winter of 1620, when a few brave

pilgrims landed on the bleak shores of New England, “It was a time for trying

the stoutest hearts.” But the same

over-ruling Providence that preserved their lives was caring for us. A young man with a load of frozen pork, on his

way to Mankato, was stormbound in our town, and the people gladly bought his

whole load and considered it a Godsend.

I never heard what the people of Mankato thought about it.

The town would

soon have recovered from the gloom which that winter had cast over it, but

another blow was in store for it. The

Indian massacre at Spirit Lake effectually retarded all growth, and it was with

difficulty the few settlers then living here were induced to stay. A fortress was commenced but never

finished. After they had done their

terrible work at Spirit Lake the Indians left, never to return. A short time before we came to Algona they

had made their last visit to this place.

About one hundred of them had departed for new hunting grounds just

before we arrived, so that we have never had even a glimpse of the

savages. Before they left they assembled

on the knoll where the D. H. Hutchins house stands, and gathering a number of

pebbles, made a circle of them on the ground and marked each pebble with

red. We never could interpret the

meaning of the symbol.

A dead calm was

resting on the place; all immigration has ceased; building was suspended; the

saw mill was quiet. The ordinarily

routine of living went on. We raised our

crops that we might have something to eat, we ate that we might raise

more. Our churches and schools, lyceum and

social functions were faithfully attended.

We gradually grew accustomed to our quiet mode of living, always hoping

that the lull would, ere long, be broken.

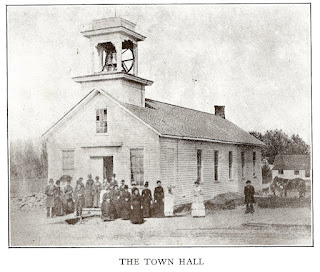

But in ’61 a cloud came up from the South and for more than three years

its black hulk hung over us. Fort

Sumpter had been fired upon and quickly the discharge was felt in Iowa

homes. Civil War was upon us and some of

our number must go. Meetings were held

in the Town hall and speeches were made, firing the hearts of our young men

with enthusiasm. About twenty, I think,

left their homes and friends for the front—three came back. A few of them were killed in battle, but the

greater number died like rats in the trap.

Under orders of a half-drunken captain they were hurried off, as soon as

anyone showed any symptoms of being sick, to a poorly managed hospital, where

they promptly died after a few days treatment.

After the war

was ended and peace again settled over the land the thoughts of the people once

more turned westward and Algona received a fair share of the immigration. It has since increased steadily but rather

slowly in population and wealth till the present year, 1911, which is now

witnessing its most rapid growth since the summer of 1856.

I am afraid my

story is indeed tiresome, but when those old time memories are called up for

recognition they come trooping in such numbers and so rapidly it is difficult

to leave any unnoticed.

Emma

Heckart

Zephyr

Hills, Florida, Nov. 27, 1911

Mary Emmeline Heckart began teaching

school at the age of 17 making $20 per month.

She continued to teach for forty years.

Although she never married, she helped to raise two orphaned nieces,

Carrie Beall and May C. Walker. She made

her final home in Zephyr Hills, Florida, where she died on August 4, 1937.

Until

next time,

Jean,

a/k/a KC History Buff

If you enjoyed this

post, please don’t forget to “like” and SHARE to Facebook. Not a Facebook

user? Sign up with your email address in the box on the right to have

each post sent directly to you.

Be sure to visit the

KCHB Facebook page for more interesting info about the history of Kossuth

County, Iowa.

Reminder: The posts on Kossuth County

History Buff are ©2015-16 by Jean Kramer. Please use the FB “share”

feature instead of cutting/pasting.