Nancy

Yeoman, a good friend and researcher,

emailed me some articles she had come across while researching another matter

that she thought might make good topics for blog posts. I have to agree (and I am glad that someone

else gets distracted from the research project at hand whenever another

headline catches their eye and lures them in).

This particular story is a tale of love and marriage, unhappiness and

parting, murder and suicide—a difficult story to tell, but a reminder that

violence is not new to our society.

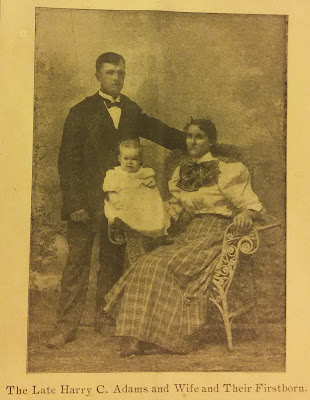

THEIR STORY BEGINS

Etta

Campbell and Harry Adams were married November 25, 1895, at the home of Etta’s

father, Zane Campbell. The Campbells

farmed just north of Woden in Grant Township, Winnebago County. The two met when Harry was working for a crew

putting up hay in the area. He had grown

up in Algona, the son of Mr. and Mrs. William Adams, long-time residents who

lived south of town.

The

couple went on to have two daughters, Dora and Vera, and to all outward

appearances, the marriage was a happy one.

Harry was a hard working young man despite a handicap. Caught in a cyclone while living on the farm,

his right arm had been badly broken. Due to the manner in which it was set, after

it healed it was shorter and a little crooked.

This disadvantage did not slow him down though as he had jobs haying,

driving teams, picking corn and cutting wood.

The nature of the work he performed was that of a laborer and it appears

that the family may have struggled financially to some extent.

TROUBLES SURFACE

As

we all know, appearances can be deceiving as no one knows what goes on behind

closed doors. The couple became

estranged at some point and so by September of 1902, Etta Adams decided to

leave her husband and children and did so in a way that caused criminal charges

and public embarrassment.

Her

intention was to leave town and quietly make her way to Elmore, Minnesota,

where she intended to find a job.

Sometime prior to her planned sole departure, she met a young girl by

the name of Loretta Phillips who for whatever reason wanted to run away from

home. Etta consented to take her along

even though she was only 13 years of age. Etta hired a driver by the name of

Joe Fraser to take them to Elmore, Minnesota.

Leaving

Algona on Monday, September 8, 1902, they traveled on back roads mostly at

night to avoid being found. During the

day they would rest at hay stacks to avoid detection. They reached Ledyard on Thursday, September

11th. It was there that

Marshal Fred Jenks spotted them, having been alerted of outstanding warrants

for the two adults. He arrested both

Etta Adams and Joe Fraser who were charged with enticing away a child under the

age of 14. The three were transported to

Algona by the 2 o’clock train. All three

appeared before Justice of the Peace Raymond.

Loretta was sent home to her parents and bond was set at $200 each for

the two adults. While in the court room,

it was observed that none of the three seemed much concerned, especially Etta

who chewed gum during the entire proceeding.

She did declare in open court that she never would go back to live with

her husband again. Shortly thereafter, her

bond was posted by Harry and she did return to live with him.

In

an affidavit filed the following week in the case against her, Etta stated that

she had been having trouble with her husband because he got drunk and abused

her. She stated that she had told him

that she was going to leave him. Her

affidavit, along with similar statements from Loretta, Loretta’s mother, Joe Fraser

and Harry Adams, stated that neither Etta nor Joe enticed Loretta to leave her

home and that she had accompanied Etta of her own free will. All charges were dismissed against both Etta

and Joe, but the damage had been done to their reputations.

SEPARATION AND A DIRE DECISION

Although

they had reconciled, the young couple continued to have problems. They were living in a house near the

Milwaukee depot and Harry was making $35 per month working for the Algona

Milling and Grain Company delivering coal.

Following the incident involving her arrest, Etta declared that the

whole town was gossiping about her and she wanted to move. Harry agreed, quit his job and sold off their

furniture and belongs in preparation for the move. Etta announced that she was leaving to look

for a more desirable location. She then

left without telling Harry where she was going.

It is not known how much time passed, but eventually Etta was spotted in

Fairmont and Harry went there immediately.

He brought her back to Algona where they rented a small home in the

western part of town. Etta was still

restless and unhappy. It was intimated

that male callers came to her home while Harry was at work.

On

Thursday, December 18th, Cora Whitson came to call. Mrs. Whitson had quite a reputation as she,

along with Blanch Ferguson, had been charged with prostitution the previous

year and had been run out of town. Cora

had just recently returned. How these

two women met or formed a friendship is unknown, but they both must have been

hungry for some adventure. They hatched

a plan to meet the next evening. With

her husband gone chopping wood for Ambrose Call, as soon as Etta had her two

small daughters tucked in bed on Friday evening, she left. Upon his arrival home and finding his wife

gone, Harry woke his children asking where their mother had gone. They stated that she had gone off with

“jingle bells.” Knowing his daughters

used that term for the sound of sleigh bells, he took off for the livery stable

where he found the two women preparing to leave. Adams begged his wife to return home, but she

rebuffed him and swore at him. Etta set

off with Cora and didn’t return until 2 a.m.

Where they had been and what they had done was unknown but upon her

return Adams packed up his two little girls and all of the belongings he could

carry and made his way to the home of his parents.

Harry

met with Cora several times over the next few days, begging her to come back

and offering his forgiveness. He asked

to take her to see her parents for Christmas, but she refused, saying they all

could go to hell and that she did not care for Harry or them. After the final rejection, it appears that

Adams decided that if reconciliation was not possible, he would bring a

conclusion to his suffering by ending both of their lives.

DAY OF RECKONING

Harry

and his daughters were living with his parents whose home was south of town

across the river. Etta moved in with

Cora Whitson who was living with her two small children in a couple of small

dirty rooms in the old college building which had been turned into a rooming

house after its move to the corner of Dodge and Nebraska streets. It was there that Harry came with his shotgun

on his shoulder after having Christmas dinner with his family and writing his

suicide note.

|

| The site today where the old college building sat in 1902 |

He

confronted her one more time asking that she come home and change her mode of

living, but she refused. The two began

to argue loudly and Mrs. Whitson looked in to see that Adams had his wife on

the floor and was hitting her. Etta cried out, “Harry I will go home if you let

me loose.” A moment later Whitson heard

a shot and again looked in to see Etta lying face downward on the bed, shot to

death. She ran to get help and then

heard a second shot. When she returned

she saw Harry’s dead body sprawled on the floor.

The

news articles of the day were quite graphic in their description of the bodies

and the crime scene, leaving little to the imagination. The suicide note was printed in the newspaper

in its entirety including his last words to his children: “Poor

little Vera and Dora. I hate to leave

you.”

Harry’s

body was taken to his parents’ home where a funeral was conducted by Rev. R. T.

Chipperfield the following day. He was

buried in Riverview Cemetery. Etta’s

father, brother James, and brother-in-law Dick Gibson came down from

Woden. They took her remains on the

midnight train as far as Burt where they had a team waiting for them. By early Saturday morning Cora Whitson had

also left town.

Newspapers

often took advantage of tragedies such as these to wax eloquently on moral

turpitude and this instance was no different.

In the January 2, 1903 edition of the Algona Courier, the following was

written:

“It

would be difficult to imagine a scene from which a more impressive lesson could

be drawn as to the value of virtue and right living than the scene of that

tragedy. The dirty little room; the two

mutilated bodies; the spattered blood and brains; the wretched woman who was to

some extent to blame for the extinction of the two lives in another dirty room

with her dirty little children huddled about a stove. It was such a place that Mrs. Adams preferred

to her own humble home. It has been

truly said that virtue is its own reward.

No matter how poor the home is if fidelity and virtue abide there it may

be in a measure happy. Its occupants may

have approving consciences and self respect and the respect of others. Even in dire poverty children may be reared

to reverence religion, truth and virtue and conscious of the rectitude of their

lives they become strong, self respecting and wholesome members of

society. But in households where there

is no religion or moral training there is seldom virtue and the ornaments which

it bestows.

“Young

women and young men too should be warned by the fate of Mrs. Adams and her

husband and also by the fate of Mrs. Whitson and Mrs. Ferguson and all such

unfortunates. When the jewel of virtue

is lost womanhood is degraded too low for contemplation. Let her who would be happy, respected and

love preserve that jewel from stain as she would preserve her life from danger.”

Until next time,

Jean

If you enjoyed this

post, please don’t forget to “like” and SHARE to Facebook. Not a Facebook user? Sign up with your email address in the box on

the right to have each post sent directly to you.

Be sure to visit the

KCHB Facebook page for more interesting info about the history of Kossuth

County, Iowa.

Reminder: The posts on Kossuth County History Buff are ©2015-2017 by Jean Kramer. Please use

the FB “share” feature instead of cutting/pasting.