The eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the

eleventh month, 1918. The end of the war

to end all wars. Today we celebrate the 100th anniversary of that historic

moment when the armistice agreement took effect, ending WWI. The first Armistice Day was celebrated in

1919 on November 11th. In

1926 Congress passed a resolution for an annual remembrance on that date and in

1938 it became a National holiday. President

Eisenhower changed the name from Armistice Day to Veterans Day in 1954. A full century later, we continue to commemorate those who have served our nation in the military.

Carl Hagg was the first Algona soldier killed in

action during WWI. He along with his

brother, Arthur, and cousin, Fred Hagg, served bravely during the war. It is an honor for me to share their story. My thanks to Brian, Kent and Rex Hagg (Arthur's grandsons) for sharing family photos and memorabilia with all of us.

Carl and Arthur were the two oldest sons of

Charley and Hulda Hagg. They grew up on a farm in Union township just north of

Algona. Both of their parents were

immigrants from Sweden. They married

here in Kossuth County in 1887 and settled on the farm. Swedish was spoken at home until the boys

were old enough to go to school when English became their second language. Charley and his wife were hard workers and

saved as much as they could to put back into the farm. Unfortunately about the time the youngest

child was born, Charley contracted tuberculosis. He traveled as far away as Chicago seeking

treatment, but never found a cure. He

died in January of 1908 after several years of illness.

Fred was the son of Peter Hagg, Charley’s

brother, and the two families were very close.

Although the boys were cousins, they spent so much time together they

felt like brothers.

As the oldest son, it became Carl’s

responsibility to keep the farm running during his father’s illness and

following his death. He was 18 years old when Charley died—old enough to take

on a man’s responsibilities. Just two

years younger, Art pitched in too to help with all the chores and farming

duties. Their four younger brothers

helped as they could but the youngest, Hjalmer, was only four years old when

their father died.

Working together they farmed the land owned by

their mother and rented some additional farmland which helped them to

expand. During the years before the war

they started a milk route in Algona which fit into the operation very well. When the war broke out in Europe in 1914,

they watched with interest but it did not appear that the United States would

enter the war. As time passed though,

U.S. government policies began to change and they came to believe it would not

be a matter of IF the United States got involved, but WHEN.

When the time came, Carl, Arthur and Fred all

went up to the draft board together on June 5, 1917, and registered. Although she never talked about it, as the

mother of six sons, Hulda Hagg must have worried that several of her sons might

be called into action.

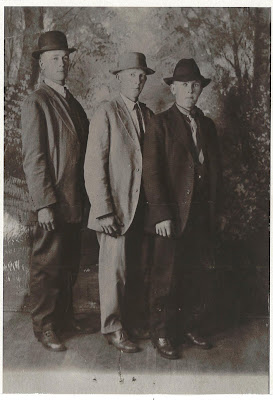

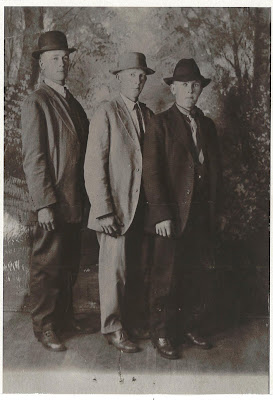

|

| Arthur, Carl and Fred Hagg |

The first two contingents were called in

September of that year but none of Hagg boys were included. They knew many of the men who left and were

part of the crowds that gathered to send them off. It was such a patriotic time! The whole town was so supportive of those who

were called to serve.

As news of the fighting began to filter back

to the States, it became apparent that one or more of the Haggs would soon be

drafted. On April 8, 1918, Fred and Carl

were inducted. They were sent directly

to Camp Dodge where they became privates in the 163rd Depot

Brigade. Camp Dodge was a bustling city

of its own—neither of the boys had ever seen so much activity! They had just settled in and had begun basic

drilling when after a mere two weeks they were transferred to Camp Mills, New

York.

|

| Carl Hagg in his uniform |

There was such a need for troops in France

that they had virtually no time for training there either—on May 3rd

they boarded ship out of New York harbor headed for France after having been reassigned to Company G of the 138th Infantry Regiment of the 35th

Division of the National Guard. They had

only been in service 25 days. By July

they would be on the front lines.

Carl wrote frequently to his mother but never

wrote much of his war experiences. Of

course all mail was censored to prevent the enemy from receiving any military

strategy, but he likely tried to shield her from the horrors that he was

witnessing.

Life in the trenches was dreadful. On several occasions Carl spent as many as 20

days in a row in them. When not fighting

the enemy, they had to fight off rats and other vermin who wanted to make their

homes there. Lice were a constant

nuisance. When it rained the trenches

would fill with water and turn to mud.

Many soldiers suffered from foot rot as a result. Being confined together did one thing

though. They did get to know their

comrades well as they spent any idle time they had talking about home and what

they were going to do with their lives when they left that forsaken place.

Carl actually saw service in the trenches

several days before Fred did, but by mid-July of 1918 they both felt like old

veterans. In a letter home to his father

Fred wrote, “I have been in the front line trenches for two weeks. That sure is some place. Had my rifle hot more than once. Now I am at resting camp but may be called

back at any time. . . It takes good eyes and ears to be in No Man’s Land. I have been over here a few weeks now but

will be glad when it’s over with so I can come home again for this is no place

for me.”

Arthur Hagg, Carl’s brother, and Gustaf Hagg,

Fred’s brother, were drafted with the local contingent that left in July of

that year. They were sent to Camp Gordon

as privates with the 330th Infantry Regiment, but Arthur was later

reassigned to Company A, 11th Infantry Regiment which was part of

the 5th Division while Gus fought with Detachment 12A of the 337th

Infantry. They did not receive much

training either and sailed for France in late August, 1918. After arriving in September, Art wrote to

Carl, but was unsure if he was receiving the letters as he received no

response. Both Gus and Art were hoping

to meet up with Carl and Fred in France.

What a reunion that would have been!

As word filtered down through the ranks, Carl

learned that a big push would soon be coming against the enemy. He did not have long to wait. On September 26, 1918, the battle of

Meuse-Argonne began at 5:30 a.m. after a six-hour long bombardment. The 138th Infantry led the

division into battle. They stepped off a

line near Vasquois Hill and advanced toward Charpentry under cover of darkness,

vegetation and the combination of fog and smoke created by the earlier cannon

bombardment. Suddenly they were caught

out in the open as they made contact with the German line.

Enemy fire came in from all directions. Fred saw Carl fall around 11 a.m. and rushed

to his side. His last works were, “I

guess I have done my duty. This is as

far as I can go.” Fred had no choice but

to leave him there and continue to fight as the battle raged on. They were able to take the enemy main line of

resistance about 12:30 p.m. with the assistance of tanks. Due to the high number of casualties, several

Battalions assembled in the town of Cheppy and reorganized. They then made another push mid-afternoon,

advancing further into enemy territory.

This battle proved to be a crucial push against the Hindenburg Line, but

the casualties were so numerous that it came at a very high price.

The extraordinary number of casualties from

this battle caused notification of next of kin to be delayed. Thinking that Carl’s mother had received

notice of his death, Fred wrote a letter of consolation to her on October 7th,

letting her know that he had been with Carl in his final moments. Sadly, his letter was the first news she had

received about his passing. She

continued to hold out hope for his return until a telegram finally arrived from

the War Department in late November regretfully informing her of Carl’s death.

Arthur did not learn of Carl’s death until sometime

later. He too fought in the Meuse-Argonne

offensive for several weeks just prior to the signing of the armistice on

November 11th. He remained in

France until the following July when he sailed for home.

The fighting also ended for Fred when the

armistice was signed. He left France the

following April and was discharged from the army shortly after his return to

the States. He was so happy to come home

to Algona. On July 29, 1919, a

Homecoming celebration was held for veterans in downtown Algona. A huge victory arch had been constructed in

front of courthouse square. Fred was one

of over 600 servicemen who marched in the parade led by the 168th

Infantry (Rainbow) Band. The parade

wound through Algona all the way to the fairgrounds where a special dinner was

served in Floral Hall for men in uniform.

Many events were held that day including a baseball game, harness races,

and two different dances with spectacular fireworks to close out the day.

|

Hagg Post #90

American Legion building |

When the American Legion was established in

Algona, the Hagg family was so touched that it was named “Hagg Post Number 90”

in honor of Carl’s ultimate sacrifice.

In fact, when his body was eventually returned to the States for burial

in 1921, it was first taken to the Legion Building for examination. Members of the Legion acted as pallbearers, marching

first to the church with the remains and then to his grave following the

service. They made sure that Carl

received a full military funeral including firing a salute and sounding Taps.

Fred later married Dora Heiderscheidt and

worked for the City of Algona most of his life.

He died at the age of 81 in 1975 and was buried in Calvary Cemetery in

Algona.

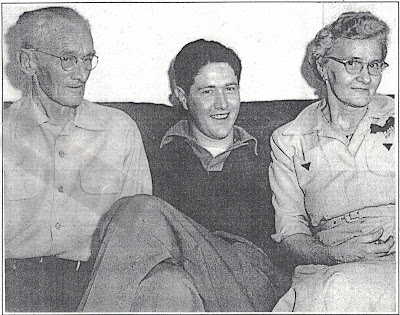

A few years after his return, Arthur married

Emma Johnson and they became the parents of five children—two girls and three

boys. He farmed until his death at age

52 in 1944.

Just 29 years old when he died, one can only

imagine what Carl would have done with his life. Instead he rests peacefully near his parents

in Riverview Cemetery, far from the French countryside where he bravely fought

and died.

Following the end of the war, a promise was

made by a weary world. That promise was

symbolized by a poppy and the words, “Lest We Forget.” Unfortunately, the meaning of that promise

has faded over the last 100 years. Today,

please spend some time thinking about the sacrifices made by the brave men and

women who have served our country in military service, thank them for their service, and the next time you

purchase a memorial poppy, renew your pledge to never forget.

Until next time,

Jean

If you enjoyed this

post, please don’t forget to “like” and SHARE to Facebook. Not a Facebook

user? Sign up with your email address in the box on the right to have

each post sent directly to you.

Be sure to visit the

KCHB Facebook page for more interesting info about the history of Kossuth

County, Iowa.

Reminder: The posts on Kossuth County

History Buff are ©2015-18 by Jean Kramer. Please use the FB “share”

feature instead of cutting/pasting.