Merrill Call is a grandson of Asa

Call. He is buried along with four

generations of Call family members in the tomb located in Riverview

Cemetery. Today I want to share the

story of the heinous crime that took his life at the age of 26.

FROM ALGONA TO SIOUX CITY

Born in Algona May 8, 1878, Merrill spent

much of his youth here until his parents, Asa Frank Call and Lucina Hutchins

Call, moved to Sioux City when he was 10 years old. He never lost his love for Algona and visited

often – especially his mother’s parents, Mr. and Mrs. D. H. Hutchins. He was an active cyclist—in fact when he was

16, he rode a bicycle here from Sioux City, making the trip in about 16

hours. It is hard for me to imagine the

condition of the roads that he had to travel on—it certainly would not have

been an easy trip. Earlier that same

year, he placed third in the five-mile bicycle race at the Kossuth County Fair

and won a fine sweater. Don’t you think that

given his love of cycling, he would have been an active participant in RAGBRAI if

he was alive today?

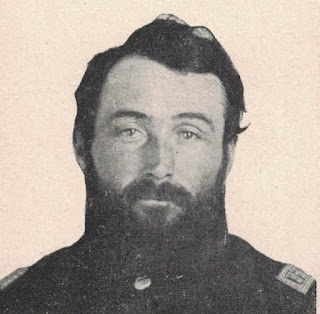

|

| Merrill Call |

He completed high school in Sioux City

and later studied engineering at Purdue University. At the age of 20 he became the superintendent

of the Sioux City street car lines.

In 1903 Merrill married Lucy Tolerton

of Toledo, Ohio, and the two later had a daughter, Mary. After their marriage, he agreed to take a job

in the Tolerton family business. Lucy’s

father, in company with a number of Toledo associates, owned considerable

mining property located in Yaqui Indian country in the state of Sonora,

Mexico.

TOLERTON MEXICAN INVESTMENTS

Among the holdings of the group in the

Yaqui country was a smelter at Toledo camp, 35 miles from the nearest railroad

station. Merrill had recently been made a

manager at a salary of $10,000 per year-more than the pay of a United States

Senator.

A trip was organized in January of 1905

to inspect some nearby mining properties for the Yaqui Mining and Smelting Company,

of which his father-in-law was a stockholder.

There were eight members in the party, which included four other

employees, two Mexican drivers and Charles Tolerton, his wife’s cousin, who

came along as a pleasure trip. It was on

this trip that Merrill met his fate.

Realizing the unsettled and restless

condition of the Yaquis, before setting out on the expedition, they had put in

a request for a guard. The Mexican

authorities declared an escort to be unnecessary on account of the number in the

party and the fact that the Indians were not particularly hostile to Americans. Determined to reach the mines at any cost

they set out without the guard, heavily armed with six shooters. Merrill

himself carried a shotgun as did most of the rest of the party. Charles also carried a rifle and a dagger.

They had completed the inspection of

properties at camp Toledo and were returning in the late afternoon to La

Colorado, a distance of about 75 miles, traveling in two four-horse

stages. Call was traveling in the second

stage with Charles and two others.

They proceeded along a broken road,

each side of which was thickly grown up with mesquite grass. The road itself was much traveled and not

considered very dangerous. Great

quantities of silver bullion were hauled over the road every day to the

railroad for shipment. Unaware of any

lurking danger, they proceeded along the desert road. The horses were trotting slowly, the Mexican

drivers sitting on top. A low hill arose

from one side of the road, which passed around the foot of the hill in a

winding course, and was lost in the distance.

Inside the stages the men were chatting pleasantly when suddenly,

without any warning, there was a volley at close range, and bullets whizzed in

all directions.

Everybody jumped out of the stages in

an instant. Herbert Miller, a passenger

in the first stage who was familiar with the country and its dangers, yelled

“For God’s sake, boys, run! It’s the

only way you can be saved!”

A FIGHT FOR THEIR LIVES

At a ranch house where they had stopped

not long before, the members of the party had been joshing each other about

being heavily armed, and it had been generally agreed that it would be better

to make a good run than to stand and be shot in case of an attack by the

Yaquis. But at the critical moment most refused

to run. However, when Miller gave the

warning, Charles Tolerton threw down his rifle and ran. Charles, Miller and one of the Mexican

drivers took to their heels and they are the only three who made it out alive.

The Indians must have numbered 75 from

the way they fired, for bullets came thick and fast. The first volley killed the Mexican driver of

the second stage and he reeled off the rig, his body riddled with bullets. Another volley snuffed out the lives of two

party members, who fell in their tracks after jumping from the first stage. A passenger in Merrill’s stage, Walter

Steubinger, was the next victim. He was

killed after leaving the rig. One of the

four horses from the first stage was killed by a bullet from one of the rifles

and the Mexican driver leaped to the ground and made it up the hill.

At the first volley, Merrill had jumped

to the ground and took refuge behind a stump, where he used his shotgun in the

hope of affording escape to the other members of the party. He took one shot to the abdomen but was able

to struggle up to his knees and continued pouring shot into the Indians, until

a bullet in the neck ended his life.

The Indians frightened the horses and

they started up the road at a breakneck speed.

As it rounded the turn of the hill, Charles was barely able to clutch

the end gate of the wagon, and, swinging himself into the vehicle, drove with

all speed toward town with five Indians in hot pursuit, yelling and shooting as

they rode.

After traveling several miles, one of

the horses fell dead. Charles quickly leaped

from the wagon and, cutting the lead team loose from the pole of the stage, threw

an overcoat on one of the horses, and, leaping upon him, continued his mad

ride. The Indians stopped their pursuit

when they reached the stage. Tolerton

rode on to Cobachi, about ten miles from where the attack occurred. The village was made up of Mexican ranchers

who did not speak English. It took some

time to find anyone who could understand English.

Miller, in the meantime, had made good

his escape and, closely followed by the Mexican driver, hastened to a town in

another direction, running the entire distance.

He explained the attack to the inhabitants of the town and a rescuing

party was quickly made up and hurried to the scene of the attack.

When the party arrived the Indians had

escaped. The Indians had stripped all of

the bodies which had been beaten with rocks and clubs. The bodies were removed to the home of a

rancher. The next day they were

delivered under a heavy guard into the hands of an undertaker to prepare for

shipment home. It was only after all

arrangements had been made that Miller finally had his own injury treated. He had been shot in the hip and endured his

pain and suffering until he was satisfied that the bodies would be safely returned.

BODY BROUGHT HOME

|

| Merrill's mother |

Merrill Call’s body was returned to

Sioux City for funeral services. From

there it traveled by special funeral train to Algona accompanied by his wife, his

parents and other family and friends.

The funeral cortege arrived in Algona very early in the morning and the

party remained in the sleeper until about 7 am when friends in Algona sent

carriages for them and brought them to the Durdall Hotel for breakfast. His casket was removed from the train to the

Call family vault here in Riverview cemetery prior to the gathering of

friends. The interior of the tomb was

banked with carnations and roses. A

short service was conducted by Rev. Holmes.

There was a large attendance of sympathizing friends of the family at

the interment, despite the zero weather prevailing.

INVESTIGATION OF ATTACK

Although it was originally thought that

the attackers were Yaqui Indians, following the massacre Herbert Miller found

inconsistencies and continued to investigate the matter. Yaqui Indians were known to purchase their

ammunition in the United States. Empty

shells picked up on the ground at the scene of the tragedy were of the Mauser

type, which convinced him that they were purchased or obtained in Mexico as the

Mauser was very little used in the United States. He became confident that it was Mexicans -- not

Yaqui Indians -- who were responsible for the murders.

During a follow up trip to Mexico, the

Governor of Sonora demanded a meeting with Miller at which he accused him of

plotting against the Mexican government.

In fact, the Governor went on to accuse Miller himself of committing the

murders claiming that his mines were worthless and that he did not want the

rest of his party to give out a bad report so Miller had the whole party

killed. Further the Governor demanded

that Miller provide him with a statement relieving the Mexican government from

all responsibility. Of course, Miller

refused to do so.

Miller joined forces with Merrill’s

uncle, Joe Harry Call, of Los Angeles and Ex-Senator John M. Thurston of

Nebraska to pursue an indemnity claim for $450,000 against the Mexican

government. He was convinced that it was

the duty of the United States to demand instant protection for Americans from

the Mexican government. It threatened to

turn into an international incident.

THOSE LEFT BEHIND

|

| Merrill's father |

Merrill’s death was a particular blow

to his parents as he was their last surviving child -- his brother Joe

succumbed to typhoid several years before, leaving only Merrill to carry on the

family name. Many dreams of his parents

died with him. In fact, their grief was

such a strain on their relationship that they later divorced.

Following his death, his widow and

daughter first moved to Sioux City to live with Asa Frank Call, Meriill’s

father, and then moved to Sonoma County, California, where his father owned a

citrus farm. It was near that home where

his father was hit by a train and killed a few years after Merrill’s

death. Although he wished his ashes to

be scattered “as though he had never existed,” they are interred here in the

Call tomb. Merrill’s precious little daughter

Mary was Asa Frank’s sole heir.

In 1914, Lucy married Richard Kirkley. She went on to have a second daughter and

lived to the age of 97. She remained in

California for the rest of her life and is buried at Riverside, a half a

continent away.

Such a sad ending to very a promising

life.

Until next time,

Jean

If you enjoyed this

post, please don’t forget to “like” and SHARE to Facebook. Not a Facebook

user? Sign up with your email address in the box on the right to have

each post sent directly to you.

Be sure to visit the

KCHB Facebook page for more interesting info about the history of Kossuth

County, Iowa.

Reminder: The posts on Kossuth County

History Buff are ©2015-17 by Jean Kramer. Please use the FB “share”

feature instead of cutting/pasting.