Last

month I was scheduled to present a program on local history at the Water’s Edge

Nature Center located on Smith Lake, north of Algona. However, influenza had other plans for me and

I had to reluctantly ask that the program be postponed. Trust me, you would not have wanted to be

around me. I didn’t want to be around

me. The wonderful staff at Water’s Edge

were very understanding and graciously postponed the program for a month to

allow me to recover. So we are going to

try again this Thursday, March 9th, at 1:00 p.m. The program will be about some of the

adventures of William Ingham, one of the earliest settlers in Kossuth

County. The program is open to the

public so if you are hankering to take a step back in time, come on out.

In

keeping with the Ingham theme this week, I thought I would share a story or two

that I was not able to include in the program.

The story “Big Elk Antlers” comes from a book entitled, “Ten Years on

The Iowa Frontier” written by Harvey Ingham, William’s son. Here is that story:

BIG ELK ANTLERS

|

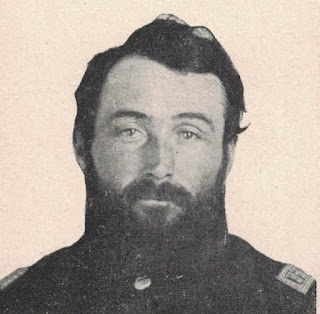

| W.H. Ingham when he served in the Northern Border Brigade |

When

the storm was over, bringing out the home-made snow shoes of the winter before,

Seeley and Ingham set forth on an elk hunt. After going up the Black Cat from

their cabin to the grove now known as the Frink Grove, they came upon a buck

elk carrying the largest antlers they had ever seen. Of their efforts to capture those antlers Mr.

Ingham writes:

“We saw a fine buck

standing some thirty rods back from the creek, within easy rifle range from a

tree we had selected from which to approach.

He was small of size but carried the largest and most perfect set of

antlers I have ever seen. We went around

the creek channel some rods on the leeward side, and then turned down as far as

we thought it safe to walk. We then

crept on the wind swept ice. When within

some four rods of the tree we saw elk ears moving on the crest of the bank some

eight feet above us. As we came to the

tree we ran into a number of does on the ice below the bend and they saw us as

we saw them. There was now nothing for

us but to rush the steep bank in the chance of getting a shot at the buck before

he could take the alarm. We sprang to

our feet and started up the bank. When almost to the top we saw the old buck

standing unconcerned within short range. Just then my feet slipped and when I

stopped my face was much nearer the ice than I cared to have it. Seeley had fared no better. By this time the elk were crashing through

the brush. We rushed again for the bank

and this time made it, only to see big antlers disappearing over the ridge not

far away.”

As

it was already growing dark, and too late in the day to think of following him,

the hunters turned back to the cabin, fully intent on resuming the hunt in the

morning. They were up early and started

off by moonlight, and found their elk bunched together on the prairie not two

miles from where they had been the night before. The buck with the antlers was alert and on

the windward side of the herd. He became

restless as the hunters neared and they were forced to shoot at long range,

killing a young buck. It did not take

them long to discover that those big horns were the reward of sagacity and

watchfulness on the part of the wearer.

After a long pursuit they sent the dog out after the elk in the hope to

scatter the herd. He killed another

young buck, and it being time to return they decided to drag the two elk to the

cabin. Mr. Ingham writes: “Seeley

always referred to this afterwards as the hardest thing he ever did.”

On

reaching the cabin they fully decided to go again in the morning with loaded

sleds and pursue big antlers to a capture, but when morning came Seeley found

he had been lamed by the work of the day before. It took some arguments to keep Mr. Ingham

from setting out alone, and frequently later he expressed regret that he was

dissuaded. He believed that alone he

could have captured the elk.

ANDREW SEELEY’S MEMORIES

Mr.

Seeley writes: “The winter of ’56 and ’57 will be remembered by all living in the

west. We did some good traveling on snow

shoes that winter. We went up the Black

Cat Creek in December, saw about 30 elk, wounded one. As it was late in the afternoon we thought it

best to leave them till morning and come home.

The elk were not over one-half mile off when we started for home. The next morning we were on their track

before it was light enough to see the tracks plainly. We came up to them between 9 and 10 o’clock,

killed one and left it lay and followed the rest for quite a distance and

killed one more, then it was noon. We

found a corner stake which said we were 15 miles from home. The snow was so deep we couldn’t get out with

a team or we might have killed all of them, as they were very tired. We had all we could get in with. They were not the largest, would have weighed

perhaps 200 pounds each. We did not

think we could get them both in. We

started with the last one we killed, snaked it to where we left the first

one. They dragged very easy on the start

but got very heavy before 10 o’clock. At

night when we made for Mr. Reibhoff’s for supper, which Mrs. Zahlten, then Miss

Reibhoff, got up for us. It was good,

you bet. I didn’t get mine quite to the

house. I left it on the ice in the

creek, gun and all. Peter and John

Reibhoff had to pull them a little ways.

He said he didn’t see how we did it. We were very tired and our feet got

very sore. It was fun on the start but

it got very old before we got through. I

think it the hardest day’s work I ever did.

We had snow shoes. I wanted to

leave them out eight miles; you that know the other fellow (Mr. Ingham) know the reason we did not. He was always tougher than I was and I

thought I could stand a little hardship those days.”

Can

you imagine dragging a large elk eight to fifteen miles across deep snow while

wearing snow shoes? I never cease to be

amazed by the super human feats some of these pioneers were able to pull

off.

THE TUTTLE WHISKEY BARREL

I

thought I would include one more brief story. At the beginning of the elk hunting story

there is a reference to the “storm that cached the Tuttle whiskey barrel.” I had not heard of that before and it made me

curious.

The

Upper Des Moines, of Algona, told the story of Mr. Tuttle’s troubles and

recalled this incident: ”Mr. Tuttle was a tall, heavy frontiersman,

pretty well along in years, who in the spring of 1856 had pushed north to a

little lake in southern Minnesota, which the Indians, with some sense of

beauty, had named ‘Okamampedah’, but which he succeeded in having known as

‘Tuttle’s Lake’, by which plain and unornamental designation it still holds its

place on the map. After locating his

family he had gone south with his boys for his winter’s supplies, and on the

last day of November arrived with his wagons at the Horace Schenck cabin. Mr. Schenck was pretty well fixed for the

winter and with characteristic hospitality he entertained his visitors. The last day of November was Saturday and it

had been one of those beautiful days that so frequently ushered in the fiercest

blizzards. In the evening a light snow

was falling. In the morning the snow was

coming faster and the wind was rising.

After some debate Mr. Tuttle decided to try for home. He succeeded in dragging his wagons into the

ravine northwest of the Reibhoff grove, and unhitching the teams turned in at

the John James cabin. Sunday night the

storm was at its height. All day Monday

and all day Tuesday it continued unabated, and although the break came on

Wednesday nobody ventured forth until Thursday, and then to look upon the heaviest

coating of snow ever seen by a white man in Kossuth county. The ravine in which the Tuttle wagons had

been left was drifted full. No trace of

the wagons could be discovered. The fact

that one of the chief items of Mr. Tuttle’s supplies was a barrel of whiskey

stirred him to great anxiety. The

thought of allowing that barrel of good cheer to lie buried all winter was too

painful to the old gentlemen, and the ingenuity of the settlement was called

upon to locate the wagons. By cutting

poles and pushing through the snow the wagon with the barrel was at length

found. Thereupon a well was dug directly

over the barrel, and during the remainder of that long winter the well was kept

open. Succeeding snows increased the

depth until finally a ladder was needed, which proved to be a temperance

measure in its way, as it was not safe at any time during that winter to be

incapacitated to clamber out of the well.

The Tuttles lingered until spring.

Finally the old gentleman insisted on starting for his home on foot,

dragging a hand sled with a jug and some other cargo.”

I

hope to see you on Thursday. Until then,

keep your whiskey barrel from being buried in the snow.

Until

next time,

Jean

If you enjoyed this

post, please don’t forget to “like” and SHARE to Facebook. Not a Facebook

user? Sign up with your email address in the box on the right to have

each post sent directly to you.

Be sure to visit the

KCHB Facebook page for more interesting info about the history of Kossuth

County, Iowa.

Reminder: The posts on Kossuth County History Buff are ©2015-17 by

Jean Kramer. Please use the FB “share” feature instead of

cutting/pasting.

No comments:

Post a Comment